CHAPTER FOUR

THE CRUCIFIXION

The stone is about to fall,

and its ripple effect

reach the farthest star.

I

SCENES FROM THE PASSION

The Week of All Weeks

From the time Jesus is twelve until he presents himself to John for baptism, the Gospels are silent. Similarly, the Apostle’s Creed skips from “born of the Virgin Mary” to “He suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried,” suggesting that all that comes between is preparation for the seven days out of all time to be known as Holy Week. Symbolically parallel to the seven “days” of creation, the “passion week” is in reparation of the breech that had come between the divine and the human.

The focus is now on the sequence of events that culminates with the Crucifixion. In Christian mysticism, these occurrences correspond to the “rite of passage” known as the “dark night of the soul.” The outcome of this pivotal and often prolonged spiritual crisis is the “crucifixion” of self-will. There is another crisis Saint John of the Cross calls the “more terrible” “dark night of spirit.” The result of passing through this “night” is an expansion of consciousness that transcends the personal and encompasses the whole of humanity. Jung describes the outcome as he experienced it as when one no longer belongs to oneself but to the all.

The Triumphal Entry

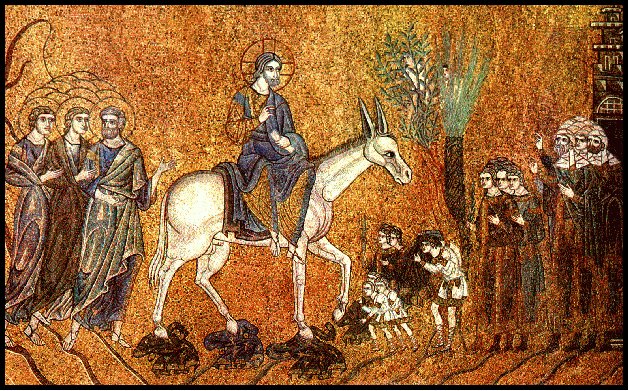

In the life of Christ, the successive events leading to the Crucifixion begin with the triumphal entry into Jerusalem. (Plate IV-1)

Entry into Jerusalem,

12th Century Mosaic

Plate IV-1

As Jesus comes riding on the back of a donkey, the crowd cries out “Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord.” This compels the Pharisees to demand that Jesus rebuke the claim of the people. Instead he counters:

I tell you, if these were silent,

the very stones would cry out. (1)

Oblivious to the gathering storm clouds, the people continue their shouts of “hosanna.” Knowingly, the stones as well continue their silent witness: of children dancing about and spreading palm fronds before the one who comes regaled as a king; a king coming in peace--on a donkey--the very same beast of burden that had carried the infant Jesus out of harm’s way in the arms of Mary. With this reentry Jesus’ life comes full circle. As “the son of man” his days are numbered, each increasing the certainty of his fate. With the high drama of the passion underway, from here on out every detail is a symbol. As one day leads to another, the branches of the palm--in Hebrew phoenix--will turn to ashes. Mary’s joy, as Simeon foretold, will turn to sorrow. But like the fabled phoenix he too will rise reborn. The palms of this Sunday will become the following Friday’s “ashes,” and be memorialized in the tradition of all Ash Wednesdays to come.

The Stones

Donkey and palms have their significance. But what of the stones who keep their silent watch? What do they know? What do the shouting people and the dancing children know that those supposed to be “in the know” don’t? And where in all this pageantry is the one Jesus calls the rock? Peter--Petros the rock--also stone, also mountain. Imagine his elation! His relief! Jesus was wrong. He does not have to die. He is going to be acclaimed king . . . and “I, Peter, will reign with him.”

Poor Petros--hard, stubborn substance of matter--he doesn’t understand the transubstantiation of matter into spirit. And so he must cling to the only Jesus he can imagine--the flesh and blood one he knows as Rabboni. In the language of symbolism, who is this Petros on whom so great an edifice is to be built?

He is the rock: the stone, the mountain, the hard substance of matter. As the knowing stones he is the created world as the container of spirit. His feminine counterpart is Sophia who, as Holy Wisdom, is the Philosopher’s Stone, the Alchemist’s opus--gold from lead, spirit from matter, meaning from existence, Self from self, Life from life,

In the Arthurian cycle the sword is in the stone. The sword of spirit is embedded in the stone of matter. The one who can extract the sword from the stone will rule the kingdom, for,

If stone is turned to bread it is consumed,

but if stone bears witness to Truth it is eternalized.

Therefore it is the rock, the stone, the mountain

--the hard, stubborn substance of matter

that cries out very God of very God.

With the dawning of this Truth the Stone is about to fall and its ripple effect reach the furthest star.

Another Garden

Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday . . . Holy Week moves on: The tables are overturned in the temple; the Last Supper is shared in the upper room; and the disciples follow Jesus into the garden of Gethsemane where the greatest act of compassion the world has ever known is about to move to center stage.

The reverence with which Christians speak of “the passion of our Lord Jesus Christ” is in recognition of a heart of flesh and blood so unbounded as to have expanded to infinity. The stones and rocks of this other garden are to witness the final dissolution of the barrier between the divine and the human, making Gethsemane the symbolic inversion of Eden. For if Eden symbolizes disobedience, Gethsemane is its opposite--obedience unto death.

At the Foot of the Mount of Olives

Gethsemane, at the foot of the Mount of Olives, is the place where the oil is pressed from the olives. It is here Jesus has come to pray--a stone’s throw or so from the temple complex where, at the very same time, those empowered to uphold the structure of Judaism are plotting to murder its purest son.

Jesus goes deep into the garden and kneels beside a large rock beneath the ancient, gnarled trees. He knows what he is up against, and asks the three disciples closest to him to “watch and pray.” Knowingly and deliberately he has overturned the tables and accused the richly-garbed priesthood of stealing money from the poor. Openly, he has called the Pharisees hypocrites and bigots. He knows the fickleness of the multitudes who just days before had acclaimed him their king. He is also mindful of the weaknesses of those close to him. As when oil is being extracted from the olives, the wheel turns and the weight of the press bears down.

The Bible says he is “perplexed” by the oppression coming over him. He continues to pray. He identifies the oppressive force. It is grief. It is sorrow. And it continues to worsen. He awakens the three who have fallen asleep, and tells them that his soul is exceedingly sorrowful, “even unto death.” He asks again for their help, that they stay awake and pray. But he also understands it is their own grief that is rendering them unconscious. He is overheard addressing “Abba.” He asks: “if it is possible let this cup pass away from me: nevertheless, not as I will, but as thou wilt.”(2)

[Then] an angel appeared to him, coming from heaven to give him strength. In his anguish he prayed even more earnestly, and his sweat fell to the ground like great drops of blood."(3)

The Agony in the Garden, by El Greco

Plate IV-2

The images of this scene are familiar from the work of numerous artists, including El Greco, who in Plate IV-2 shows the angel giving Jesus the cup he now realizes he cannot escape drinking--the “cup of salvation”--in which the purity of his life blood, like the clarity of the finest wine, will be co-mingle with the sediment at the bottom—the bottom of the human barrel.

Agonizing against the sheer weight of what is pressing in on him, he prays for strength to endure what he must. He is preparing to let down the final barriers between his light-filled mind and the twisted, fragmented, demonized, “outer darkness” of human-nature-gone-astray.

Having consumed the cup to the last bitter dregs, his struggle now is to remain consciousness. In opening his mind to the cumulative psychic pain of collective humanity, he has opened the floodgates to his heart as well to an inundation of the suffering the human race has perpetuated on one another. So overwhelming are the heart-wrenching emotions he feels, he fears it is more than he can bear. The fight to stay conscious continues as alternately he vicariously experiences what it is like to be victim, and then what it is like to be the demon-possessed victimizer. He feels the helplessness of the abused; the frustration of the disinfranchised; the anger of those who know what it is to be the brunt of injustice; the heart-breaking pain of those who have experienced betrayal; or known what it is to feel forsaken by family, friends, and most awful of all to feel abandoned by God. Gethsemane will lead to the Cross, and the Cross into the bowels of Hell. But in Gethsemane he already will have been there.

The Cup of Salvation

In the Arthurian legends, the Holy Grail is the cup shared by Christ and the

twelve at the Last Supper. In symbolism the twelve represent the different

facets or “faces” into which humanity is divided. Legend says the cup the

disciples shared was the one Joseph of Arimathea held up to the Cross and

into which he collected the blood and water flowing from the side of Jesus.

Grail--literally a crater--is a hollowed out receptacle. The

symbolism deepens as in Gethsemane Jesus opens his soul to the suffering of

the whole of humanity, and thus becomes the hallowed Grail.

Both Paul and the writer of Hebrews speak of him “becoming sin.” This is in reference to the high priest who, before entering the Holy of Holies on the Day of Atonement, is sprinkled with the blood of the sacrificial offering. So Jesus in Gethsemane is “sprinkled” by his own blood and, in his agony, enters into the Holy of Holies to make reparation “once and for all,” therefore restoring the at-one-ment between creation and Creator.

Measured in footsteps, the distance from Gethsemane to Calvary is short. In hours there is less than a night and a day between Gethsemane’s “Not my will but thy will be done,” and Calvary’s “It is finished,” and with which words the continuation of creation towards its ultimate consummation is assured.

The search for the Holy Grail, then, can be understood as the soul’s quest for union with God. St John of the Cross writes of the “Divine light” that “acts upon the soul” in order for it to be “purged and prepared for perfect union.” It is this “Divine fire” that “before it unites and transforms the soul . . . first purges it.(4) Similarly, Teilhard writes on the mystery of Christ:

God must in some way or other make room for himself, hollowing us out and emptying us if he is finally to penetrate into us. And in order to assimilate us into him, he must break the molecules of our being so as to recast and remodel us.(5)

Christ the Evolver

As Teilhard understands the mystery of the Cross, it is both to atone and transform. Whereas up to present times the primary focus of Christianity has been on “the dark side of creation,” Teilhard, looking to the future of Christianity, sees a shift of emphasis to the “luminous” side with “Christ [as] the Evolver.”(6)

In terms of the evolution of consciousness, Gethsemane is where the light penetrated and permeated the darkness, and thus enabled the evolution of creation to continue its onward and upward ascent. In this connection both Jung and Teilhard use the term “Christification.” Sanford echoes both in saying:

God’s work among us is a process, begun by Christ and completed in the deification of the human soul and the ultimate completion of the entire cosmos.(7)

The Psychological Depths of Gethsemane

Depth psychology is familiar with an experience of the psyche comparable to the crushing of olives in a press in order to separate out the pits and pulp and extract the oil. The oil, of course, is symbolic of spirit. And as the fuel of the lamps of biblical times, it is also symbolic of light. As spirit and light, oil is symbolic of consciousness. The process of separating out the oil is a metaphor for how consciousness is extracted from the unconscious.

Normally it takes some kind of conflict or pressure to give rise to a new degree of consciousness. Ordinarily this comes about as one “agonizes” or is extremely anxious about something, or concerning which one suffers relentlessly recurring anxiety attacks. The agony of the struggle becomes the crucible in which the new measure of consciousness is separated out and contained. It becomes the empty, hollowed-out place into which God, light, consciousness can enter.

The transformation of consciousness is the result of many such personal agonies. But sometimes the process goes deeper and brings to light family or racial patterns, some of which are destructively repetitive. Insight into what “comes up” often suggests or is the remedy. Deeper still and more rare are conscious mergings with archetypal and instinctual contents. From these insight is gained into the common ground shared by all human beings. To see into one’s own instinctively-rooted vulnerability is to soften one’s judgments towards others, even to having them transformed into empathy.

Embracing the Cross

Even before Jesus came under the shadow of Crucifixion, he had made metaphoric use of carrying one’s own cross. Sanford has noted that in Jesus’ day “it was the custom for a person who was to be crucified to carry his own cross to the place of execution.”

[C]arrying our own cross is a symbol for carrying our own psyche, hence for individuation. Individuation requires us to carry the burden of our personalities and our lives consciously and courageously.(8)

Thus the gospel says:

If anyone wishes to be a follower of mine, he must leave self behind; he must take up his cross and come with me.(9)

But the ultimate meaning of Jesus’ words only becomes apparent on the road to Calvary. El Greco, in Plate IV-3, draws attention to the hands that are about to be disfigured on the cross. Leo Bronstein’s commentary points out that in bearing the Cross the hands of Jesus do not touch it. He would rename the painting “Christ Embracing the Cross."(10)

Christ Embracing the Cross

Plate IV-3

The Way of the Cross

As mentioned above, Teilhard views the necessity of the Cross as for both atonement and transformation: to repair the breech of the past and to open up new possibilities for the transformation of consciousness. The ambiguity is that while Jesus suffered for all, each one nevertheless is called to bear a portion of the burden of being human. For some the weight of the cross is what they personally suffer; for some their share of the burden is generationally or racially linked; while others are called to an awareness of suffering that constrains them to co-mingle their lives with the hungry, the homeless, and the ill.

The yoke, the yoga, the work of the Cross is light, i.e.,

consciousness--“My yoke is easy, and my burden is light."(11) Therefore, “to be crucified with Christ” is to become conscious of the

human condition--in oneself and in others. Being “yoked to Christ” is the

Gospel explanation of how suffering--whether borne or inflicted, knowingly

or unknowingly--is lifted to the Cross. Thus understood, the way of the

Cross is the willingness to accept a portion of responsibility, not just for

conscious acts and omissions but for unconsciousness as well--one’s own and

others’. It is to know and affirm, simply and without exception, that all

is forgiven. And since the Cross intersects time and eternity, its work

extends both backward into the past and forward and into the future.

Living from the Center

Psychologically understood, to embrace the cross is to live from the center in obedience to the inner voice of Self and in full acceptance of who one is called to be and what one is called to do. As Jesus--“the unblemished lamb”--willingly and consciously accepted what only he could do, so each must ask: What is there in life that only I can do? Jung reminds that this is a matter of “yeah saying” to life. Edinger adds,

[T]he cross can be seen as Christ’s destiny, his unique life pattern to be fulfilled. To take up one’s own cross would mean to accept and consciously realize one’s own particular pattern of wholeness.(12)

The discovery of “one’s own particular pattern of wholeness” is what Jung intends by individuation. In a spiritual sense, embracing the cross is a matter of accepting one’s unique and infinite worth in the eyes of God. In a psychological sense the task is to discover one’s innermost creative center and live life from there--not striving to be more or settling for less. In fact, Jesus levels his most severe criticism at the hypocrites who pretend to be something they are not.

II

THE CROSS AS SYMBOL

The Ancient Imprint of the Cross

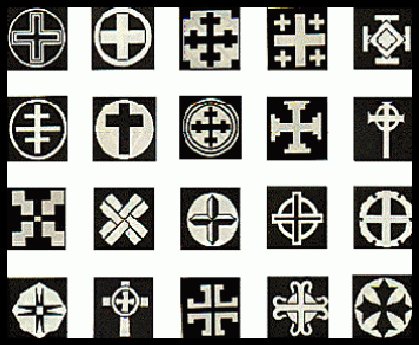

Thousands of years before the Crucifixion, the cross existed as an archetypal symbol deeply imprinted in the human psyche. It became visibly prominent in the pictographic language of early peoples the world over who incorporated it into the work of their hands for both ordinary and sacred purposes. Down through time this motif, in countless variations, has been woven, embroidered, painted, sculpted, modeled, molded, engraved, cast, and even welded by both folk and master artists alike. (Figure IV-1)

A Few Variations on the Theme of the Cross

Figure IV-1

As a universal motif, the cross is the single most essential expression of the structure of the psyche. It corresponds to the initial act of creation in emerging through a geometric progression that first divides the unity of the whole (Figure IV-2“a”) in two horizontally--what is above and what is below (“b”), and then vertically into four (“c”), the result being a sense of harmony and unity between the parts of the whole.

The Geometric Emergence of the Cross

Figure IV-2

The Highest Function of a True Symbol

Originally it was not the cross but the fish by which Christians identified themselves. The beginning of the Christian era was a time when to be a Christian was to live under the threat of crucifixion. Therefore its symbolism was not openly flaunted. But with Constantine’s official recognition of Christianity, the cross became a sign of victory, and was most often depicted in art as the risen Christ carrying the cross as a banner. Only with the advent of Byzantine art around the sixth century did the agony of Jesus’ death by crucifixion find expression in the form known as the crucifix. During the following centuries it was through this form that Christians were invited to enter vicariously into Christ’s suffering. Particularly in the richly detailed liturgical art of medieval Italy did this form of the Cross flourish. Thus it was that Francis of Assisi came to be kneeling before the crucifix at the crumbling Church of San Damiano (Plate IV-4).

St Francis at San Damiano, by Giotto

Plate IV-4

With his vision fixed upon the iconic eyes of Jesus, Francis heard the words, “Rebuild my Church.” Eventually he would understand the words as calling him to follow the Gospel as Jesus had lived and preached it. But in the meantime, he set about literally rebuilding the collapsing churches around Assisi. In his life the San Damiano Crucifix (Plate IV-5) served the highest function of a true symbol and charged his soul with a magnetism that drew others to join him in returning to the simplicity and purity of the teachings of the Gospels.

The San Damiano Crucifix

Plate IV-5

The Passion of Francis

The crucifix for Francis was a touchstone to the event it encompassed. In vicariously suffering the passion of Christ, Francis’ life was empowered. On the San Damiano Crucifix time and eternity, heaven and earth came together: Heaven’s witnesses to the event were portrayed at the very top of the crucifix; with earth’s bystanders at the very foot; while angels observed from the left and right arms. Under one of Jesus’ outstretched arms his mother Mary and the beloved John were gathered in. Under the other arm, stood the two other Marys and the centurion who had acknowledged, “Truly this is the son of God.” But the engaging focal point of the icon was in the eyes of the Christ as he passively submitted to Crucifixion. The eyes of the icon became the portal through which Francis entered into a state of ecstatic receptivity to the plan of God for his life. Paradoxically, the Cross was also Francis’ source of joy. As Paul said that he “gloried” in the cross and carried “the marks of Jesus in his body,(13) so Francis’ soul was similarly so charged by the power of the Cross that near the end of his life he too manifested the marks of crucifixion in his own flesh. (Plate IV-6)

St

Francis Receiving the Stigmata, by El Greco

Plate IV-6

III

THE INNER MEANING OF THE CRUCIFIXION

We all have to be “crucified with Christ,” .

. .

suspended in a moral suffering equivalent

to veritable crucifixion. C G

Jung (14)

The Cross of Human Nature

As the work of

transformation progresses, the ego’s role as the center of consciousness is

threatened by the Self’s higher authority as the center of the total

psyche. As the tension between ego and Self mounts a soul crisis develops

which Jung above describes as “a moral suffering equivalent to veritable

crucifixion.” Just as surely as the Incarnation led to the

Crucifixion, so in everyone the tensions inherent between “spirit” and

“flesh” become the vertical and horizontal bars of the cross upon which

human nature hangs. In the process of the second or spiritual re-birth, the

ego must endure the subjective, emotional pain of its own crucifixion.

Psychologically defined, crucifixion is the death of the ego’s will to rule;

while resurrection is the maturation of the transcendent Self whose will is

in accordance with the divine will. As crucifixion is the price exacted

from the ego and its self-will, so rebirth is the promise of the Self’s new

transcendent identity.

The Death that Leads to Life

The details of the Self’s eternal mode of being are easier to come by in the East than in the West. Exceptions, however, are found in the mystical traditions of the Sufis of Islam, the medieval Alchemists, and the Kabbalah of Judaism. They are also contained in Jesus’ teachings about how eternal life is gained. Tolstoy’s Gospel in Brief reads:

Whoever wishes to follow me, let him forsake his own will, and let him be ready for all hardships and sufferings of the flesh at every hour; then only can he follow me. Because he who wishes to take heed for his fleshly life will destroy the true life. And he who fulfills the will of the Father, even if he destroy the fleshly life, shall save the true life. For, what advantage is it to a man if he should gain the whole world, but destroy or harm his own life?(15)

And Jesus said [to Zaccheus]:

Now you have saved yourself. You were dead, and are alive; you were lost, and are found . . . .There in is the whole business of man’s life; to seek out and save in his soul that which is perishing.(16)

And again:

A grain of wheat will only bring forth fruit when it itself perishes.(17)

Crucifixion, then, is a death that leads to Life, with the biblical word translated “flesh” understood not as “body” but as the mind-set that equates reality with materiality, thus turning its back on the greater Reality. Psychologically, what is crucified is egocentricity—the ego as center--and what is resurrected is a new life lived from the Self as the center of the whole psyche, and in submission to the higher will for one’s eternal life.

The Grand Conjunction

Reaching back to the origins of human consciousness, stone and cross or cross in stone express the union of spirit and matter. The crucified body of Christ is entombed and enclosed by a stone which, with the Resurrection, is rolled away.

With the Cross--Calvary that is--as the grand conjunction of opposites, it is also the crossroads of both historic and evolutionary time. It is where heaven and earth--the eternal and the temporal, spirit and matter--come together. Similarly, in the soul’s journey, the cross foreshadows the mysterium coniunctionis--the inner marriage of the major opposites of the psyche, and the restoration of its equilibrium.

The cross is also the very structure of the psyche: its horizontal line is for the earth, the body, the feminine principle; and its vertical line for heaven, the spirit, the masculine principle. Its opus is the reconciliation of the body, mind, soul and spirit into a harmonious whole which, like the four rivers of Eden, flow from the central fountain of Life in order to restore and replenish the entire psyche. In design this is expressed by the gammadion or tetraskelion, a motif that emerges when the circumference of a circle containing a cross is broken as in Figure IV-3. The motif is also a variation of the swastika or Svasti, a Sanscrit word carrying the essential meaning of “all is well,” and which dates back to early pictographic symbolism.

The Gammadion Signifying “All Is Well”

Figure IV-3

Since to be human is to be of both heaven and earth, the cross is also the most simple and yet most profound expression of what it is to be human--to stand upright, one’s head extended toward the heavens, one’s feet gravity-bound to the earth, and one’s arms outstretched toward the horizons. In form and by nature, to be human is to bear within and without the quaternary sign of the cross.

Existence as a State of Conflict

As the Gospel calls each person to bear his or her own cross, to do so is to become conscious of what it is to be by nature part animal and part divine. This is the human state of inner duality from which there is no escape and to which each ultimately must surrender or be torn asunder. The inevitable consequence of embarking on the inner journey is to be made acutely aware of existence as the state of conflict “exemplified by the Christian symbol of crucifixion.” Going further Jung postulates that since “the soul is by nature Christian,” the pattern of crucifixion is bound to appear in the life of the individual “as infallibly as it did in the life of Jesus.”(18) Edinger, as well, affirms the deep impact of the cross on the Western psyche:

For close to two thousand years the image of a human being nailed to a cross has been the supreme symbol of Western civilization. Irrespective of religious belief or disbelief, this image is a phenomenological fact of our civilization. Hence it must have something important to tell us about the psychic condition of western man.(19)

So ancient and important a motif as the cross would have to have roots reaching into archetypal levels, and while it may seem more reasonable to assume that the cross became prominent because of the Crucifixion, it may have been that the manner in which this crucial event of human history occurred was determined by the preexistent imprint of the cross on the collective the psyche. Moreover, if the structure and dynamics of the psyche is cruciform by design then the cross, as an archetypal symbol embedded in the human psyche, is invested with the same power by which the Crucifixion led to the Resurrection, and opened the doors of new possibilities for human consciousness.

On Being Crucified with Christ

If a symbol is attuned to and empowered by the greater Reality it embodies, this would explain why for two thousand years and for so many the cross has been the most compelling touchstone of faith. It follows as well that whenever the image of the cross is activated in the psyche of an individual so as to rise to the level of consciousness, a major stage of transformation is indicated. Images of crosses, or of being crucified are evoked, and sometimes find their way into consciousness spontaneously, or through “active imagination,” or in a dream. Moreover, the crucifixion stage of the psycho-spiritual journey may stretch into years, even decades, coming and going in intensity.

Paul conveys his own experience of inner crucifixion as a conflict of wills. He observes that what he wants to do he doesn’t do and what he doesn’t want to do he ends up doing.(20) There is indication that Paul, in dealing with his conflicted intentions, discovered the effectiveness of “active imagination.” He writes of seeing himself “being crucified with Christ,” not just once but daily.(21)

The Image of Totality

As an inner process, crucifixion intensifies the conflict between the opposites of the psyche. Above its horizontal line are the conscious mind’s altruistic intentions. But below the line of consciousness is another counteractive, instinctually-rooted will with an agenda of its own. Paul names these contrary forces the “will of God” and “the will of the flesh."(22)

On the cruciform human body, the intersection where the vertical and the horizontal lines meet is at the heart. Around this center, the primary opposites of the psyche converge: upper and lower, right and left, the spiritual and the physical, the masculine and feminine poles of human nature. But at the very center, unifying and ordering the whole, is the soul’s image of totality--its imago Dei--the inner Christ as the higher Self. Thus the image of the cross is an image of totality: an ordered, contained, and completed whole and which emphasis on the unified whole is most aptly expressed in the Celtic High Cross.. (Plate IV-7)

Ninth Century Celtic High Cross

Insert Plate IV-7

Christ Crucified Between Two Thieves

In a discussion on the Crucifixion, Jung elaborates on the symbolism of the two thieves who were crucified on either side of Jesus, the one who acknowledged and the other who scorned him. (Plate IV-8)

Christ Crucified Between Two Theives, by Duccio

Plate IV-8

. . . the image of the Saviour crucified between two thieves tells us that the progressive development and differentiation of consciousness leads to an ever more menacing awareness of the conflict and involves nothing less than a crucifixion of the ego, its agonizing suspension between irreconcilable opposites.(23)

Jung emphasizes the importance of embracing the task of individuation as a “binding personal commitment.” He cautions that unless one does so consciously and intentionally the unhappy consequences of “repressed individuation” can occur.

In other words, if [one] voluntarily takes the burden of completeness on . . . [he or she] need not find it “happening” . . . in a negative form. This is as much as to say that anyone who is destined to descend into a deep pit [i.e., the deeper, collective levels of the unconscious] had better set about it with all the necessary precautions rather than risk falling into the hole backwards.(24)

One way a person can end up in a psychic pit is through the backlash effect of a projection in which the ego has become emotionally involved in defending one of its “sacred cows.” In this way the ego projects a portion of its self-worth onto an outer principle, a person, or sometimes an outworn but ingrained belief system. On this basis the ego makes unsound judgments which rebound. It ends up feeling judged, rejected, and frightfully defensive. The psychological mechanism of projection is addressed by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount:

Judge not, that you be not judged. . . . the measure you give will be the measure you get. Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?(25)

As the ego bases its sense of self-worth on outer confirmation, the Self, buoyantly free of conditioned prejudices and mores, is affirmed from within by its own sense of authenticity. But the Self also invites crucifixion by its sabbath-breaking recklessness and its table-turning disregard for “business as usual.” Thus both ego and Self end up as the two thieves to the right and left of Jesus. From their opposing attitudes, the one taunts, “If you are the Christ, then save yourself and us.” In contrast, the other confesses to “receiving due reward for [his] deeds,” but then turns and implores, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” In looking to the Christ the Self is assured, “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise."(26)

That Jesus had “a profound awareness of the reality of the psyche,” Edinger sees evidenced in his teachings:

Whereas the Mosaic Law recognized only the reality of deeds, Jesus recognized the reality of inner psychic states. . . . The gospel accounts abound [with] major psychological discoveries [such as] the conception of psychological projection two thousand years before depth psychology.(27)

The ability to recognize and withdraw a projection is particularly important when experiencing the deeper, more collective levels of consciousness. The withdrawal of a projection brings instant self-knowledge, as when a person catches sight that what she or he is seeing as “out there” is in actuality a disguised or denied aspect of oneself. In that instant the person has glimpsed the intricate workings of the unconscious mind and become incrementally more conscious. The importance of this is because

[t]he psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate.(28)

In the scripture advising the necessity of carrying one’s own cross, Jesus goes on to say that whoever is willing to be lost for his sake will find his or her true self.(29) Edinger interprets this as “if a man will lose his ego for my sake, he will find the Self."(30)

IV

A CRUCIFIXION DREAM

A dream I once had said in effect that ego crucifixion is not something imposed from without, but is an inner “rite of passage.” The timing of this dream anticipated my immersion into a long drawn-out, highly active, emotionally-charged period of inner work. My emergence from it was onto a plateau that ever since has been creatively fulfilling and relatively emotionally peaceful. Whether it lasts, or for how long, I would not venture to guess.

In the dream I was on the stage of a theater. The curtains were drawn so that what was taking place was happening “behind the scenes.” I sensed I was undergoing some kind of “initiation.” The theater was empty except about half-way towards the back a group of persons were gathered. Among them were my mother, my husband and our children. Nearby another group included my deceased father and others who, in this life, had been close to me. On the stage with me were persons I knew as spiritual companions. All were there for what was to be my “rite of crucifixion.” I observed a life-size cross with a ladder beside it. I was told that I wouldn‘t actually have to get up on the cross. The crucifixion was to be carried out “by me, to me and for me.” Knowing what I must do, I took a sword in my right hand, lifted it up, and plunged it into my left shoulder over my heart. A clear fluid, which I knew to be a vital part of me, came flowing out. There was an odor about it “like that of a living body.” I wondered how all this “vital” fluid that was being lost could be replaced. And I thought how very weak I would be until it was. With this thought the dream ended.

For nearly two decades following the dream I experienced being physically, emotionally and psychically pushed, pulled and bent out of shape, but also stretched, broadened and deepened.

What is it that enables a person to survive the ego’s “rite of passage”? Perhaps it has to do with the kind of self-honesty modeled by the one thief on the cross--what Sanford describes as “calling a spade a spade."(31) To do so is disarming to the ego’s defenses. This allows one to go behind the scenes of consciousness and observe oneself acting out the roles one has assumed on the stage of life. When self-observation is possible, insight is gained into how ordinary persons as well as actors take their cues as prompted from the wings and proceed to perform their well-rehearsed lines from scripts they have not written.

Sanford differentiates between “the ethic of obedience” and “the ethic of creativity.”

Only if a person knows what he is doing, accepts responsibility for what he is doing, and has come to terms with his egocentricity so that his goals are not self-serving, can he depart from the ethic of obedience and follow the ethic of creativity. But when this does occur, the highest and most moral life of all is lived.(32)

The ethic which Jesus outlines is that of authenticity. “Of old you have heard . . . but I say . . . ” wherein his discourse is on the inner life of the psyche. If the creative life of the Self is to be lived, its foundation must be based on an inner truth discovered through, in Sanford’s words, “psychological honesty and knowledge of one’s true motives.” Otherwise one is always in danger of “falling into the hole backwards” by reason that

Everything we do unconsciously, without awareness of our motives and without moral reflection, we must pay for later on.(33)

_________________________________

Chapter

Four Credits

Figures (by author)

IV-1 - Variations on the Theme of the Cross, partially compiled from

Horning’s Handbook of Designs & Devices, Dover, NY, 1946

IV-2 - Geometric Emergence of Cross

IV-3 - The Gammadion Signifying “All Is Well”

Plates:

IV-1 - Entry into

Jerusalem, 12th Century Mosaic, S. Marco, Venice

IV-2 - Christ on the Mount of Olives, by El Greco, 1541-1614,

(Toledo, Ohio), The Toledo Museum of Art

IV-3- Christ Bearing the Cross, by El Greco, The Metropolitan Museum

of Art, NY

IV-4- St Francis Receiving the Stigmata, by El Greco, Walters Art

Gallery, Baltimore

IV-5 - St Francis at San Damiano, by Giotto, Arena Chapel, Assisi, (Scala,

or Alinari)

IV-6- San Damiano Crucifix, 12th century, Basilica of St

Clare (Scala or Alinari)

IV-7- Ninth Century Celtic High Cross, Ireland, (Corbis.com)

IV-8- Crucifixion with Two Theives, by Duccio (Scala)

1. Luke

19: 38-40

2. Matthew 26:39

3. Luke 22:44 Jerusalem Bible

4. H A Reinhold, Editor, The Soul Afire, Meridian Books,

NY, 1960, pp 258-9

5. Christopher F Mooney, Teilhard de Chardin and the Mystery of Christ,

Doubleday Image, NY, 1968, p 124

6. Ibid, pp 113-114

7. John A Stanford Mystical Christianity, Crossroad, NY, 1994, p 300

8. John A Sanford, Fritz Kunkel: Selected Writings, Paulist Press,

NY, 1984, p 346-7

9. Matthew 16:24

10. El Greco, Text by Leo Bronstein, Harry N Abrams, NY, 1950, p 78

11.Mattthew 11:30

12. Edward F Edinger, Ego and Archetype, Penguin Books, Bartimore,

1973, p 135

13. Galatians 6:17

14. Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, C W 12, para 24

15. Luke 9:23-25, as paraphrased by Leo Tolstoy in The Gospel in

Brief, Edited F A Flowers III, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln,

1997, p 111

16. Ibid, Luke 19:9-10, p 123

17. Ibid, , John 12:24-25, p 180

18. Jung, op cit, Psychology and Alchemy

19. Edinger, op cit, Ego and Archetype, p 150

20. Romans 7:19

21. 1 Corinthians 15:31 and Galatians 2:20

22. Romans 7:21-25

23. Jung, Aion, op cit, para 79

24. Ibid

25. Matthew 7:1-3

26. Luke 23:39-43

27. Edinger, op cit, Ego & Archetype, p 133

28. Jung, op cit, Aion

30. Matthew 16: 25-26

31.John A Sanford, The Man Who Wrestled with God, Religious

Publishing Co, King of Prussia, PA, 1974, p 24

32. Ibid, p 21

33. Ibid, p 22

Go To Chapter V

Return to Higher Ground Home

Return to Murraycreek Homepage